By Aïdah Aliyah Rasheed

My grandfather, Melvin Jones Jr. and my great-grandmother Bernice Jones, in San Francisco, CA, circa 1960s, (c) jones|rasheed archive

I’m embarrassed to admit there was a time in my life that I wanted to disassociate myself from my ancestral heritage. Back in 2005 I was in the Baltimore-Washington International Airport about to fly home during my winter break from college. When I approached the counter to check my bags I was informed that my boarding pass would not be granted because my name was on an FBI list. I was alone, not sure what to do or say. As I patiently waited for the time to elapse, I had a flash back of my first encounter with racism: kindergarten. The sixth grade student helper yelled, “You can’t play with the kids because you’re black.” So I sat there on the sideline, watching everyone play on the blacktop. Other awkward quotables began racing in my mind, “You’re not black enough.” “You sound like a white girl.” “Why didn’t your parents give you an American name?” “You’re going to hell.” Eventually I was cleared to board the plane, although the trip home became a metaphor. It was a formative experience, to say the least.

I once read that children acquire their sense of self slowly as they mature into adolescents. Growing up with both Christian and Muslim family members I was always fascinated with religion. At age ten I was deciphering between theological concepts, witnessing baptisms in bathtubs, and attending prayers at the local Masjid. It wasn’t until adulthood that I began to ask my family more questions about their religious convictions. I also made lots of connections, which illustrated how resistance to injustice is part of the African American religious experience, especially in my family.

My ‘Nana’ reading to my Mother, Auntie, and other children from the neighborhood, West Oakland, CA. Circa 1970s. (c) jones|rasheed archive

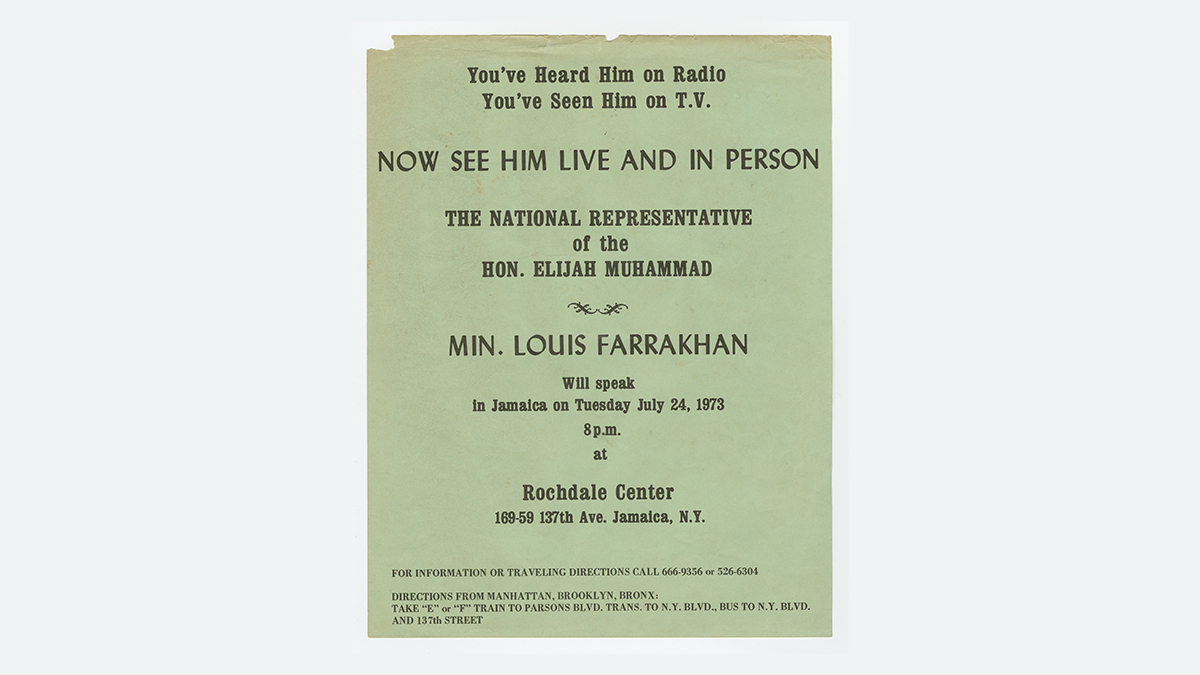

Back in the 1950’s my maternal great-grandmother and grandparents were a part of the Catholic Church. They ended up leaving the Church and gravitated towards the teachings from the Nation of Islam (NOI). Whether they were living in Detroit, Michigan or in the San Francisco Bay Area, they would hear the same message. The NOI emphasized self-discipline, self-control, and cleanliness. High moral thinking & behavior was also encouraged, such as reading literature in abundance, memorizing scientific facts, dressing in tailored uniforms, ridding off drugs and alcohol, and creating economic plans for communal sustainability.

Growing up it seemed the negative stories outweighed the good ones, and for the longest time I distanced myself from the NOI, and gravitated more towards “orthodox” teachings of Islam. It was difficult for me to disassociate the allegorical theological doctrine and the nationalism that arose from calling white people “devils.” Although after having lots of conversations with my Nana, I now understand why, at the time of inception, it was a necessary psychological metaphor. The NOI was a refuge for African-Americans seeking protection from Jim Crow laws and the Klu Klux Klan.

Top Image: Robed and hooded Ku Klux Klan members share a stage with members of the Royal Riders of the Red Robe, a Klan auxiliary for foreign-born white Protestants. Date: c. 1922; Photography Credit Unknown, image belonging to Oregon Historical Society | Bottom Image: Uniformed men in the uniform of the Fruit of Islam, a subset of the Nation of Islam, stand at attention during the Savior’s Day celebrations at General Richard Jones Armory, Chicago, Illinois, February 26, 1967. Photography Credit: Robert Abbott Sengstacke/Getty Images

***

Similar to the Nation of Islam the Black Churches in America rely heavily on communal support. My paternal grandparents stem from the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) tradition. The AME church has a history of resistance against white tyranny and racism. Richard Allen, the founder, broke away from the white church in protest of it segregating the pews. Denmark Vesey was AME and one of the founders of Emanuel AME in Charleston, South Carolina.

During my grandfather’s early years he picked cotton, and my grandmother worked on her father’s farm. Although they are devout members of the AME church, my grandparents met during a special event at St. John’s Baptist church in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Going to church was their refuge, and for two years they regularly attended services on Wednesdays and Sundays. Those were the only days they could see one another during their courtship. My grandfather once mentioned that he would risk his life walking my grandmother home. The risk: walking alone with brown skin. Despite the racism, they created a solid faith foundation. They married in 1936, and relocated their family from Arkansas to Oakland, California for work opportunities. Their love has courageously surpassed decades of difficulty, and, God willing, next year will be there 80th wedding anniversary.

My paternal grandfather, Felix Wright and my paternal grandmother, Hazel Wright in San Francisco, CA, 2014 (c) wright|rasheed archive

The first step to healing is acknowledging where the pain resides. As I continue to discover remedies for my heart, I always remember that the adversity I have faced is not nearly as difficult as my grandparents, great-grandparents, and ancestors. Instead of sulking from the discomfort of the past, the continuous news reports & videos of police killings, and the moments when we have to peer into the abyss of the depraved violence that we do to each other, I remind myself that I come from a family of lovers, believers, and survivors. If we truly believe that “all are created equal,” “with certain unalienable rights,” we will need to have more proactive conversations. May we begin to heal by sharing the truths we hold, and by doing so we encourage other people to do the same.

Aïdah Aliyah Rasheed is a creative. She lives in Oakland, CA with her husband and works throughout the San Francisco Bay Area. Ms. Rasheed is the Arts and Culture Editor of Sapelo Square.

No comments